“For politics to take place, the body must appear. […] The body has its invariably public dimension; constituted as a social phenomenon in the public sphere, the body is and is not mine” (Butler, 2004).

When I was 19, I tried to make it as a fitness influencer.

I posted every day, added “.fit” to my Instagram username and agonised for hours over getting the perfect picture to show off how toned, thin, and simultaneously voluptuous and curvy, I was. Inevitably, this involved posting in some level of undress: tight gym clothes; a sports bra; even bikini pics uploaded to several thousand followers.

Never mind that I was barely through puberty and that my account metrics showed my followers heavily skewed male; each ‘like’ felt like a tiny light being illuminated in my brain. They each felt like a tiny sigh of relief. The saves did too, although looking back it seems more likely that they were saved - not by fellow fitness-enthusiast teenaged girls - but more nefarious lurkers. Seeing how many times my posts were sent to each other would send me spiralling; wishing, wishing, that people were being kind about me. I knew they weren’t. God, how I wished people liked me.

It’s so clear now - with that impish eye of retrospection gleefully illuminating what, before, was impossible to see - that all I was doing was standing in a spotlit auditorium, looking at the blackness of an audience I knew was there but could not see and shouting: “Like this? If I do it like this will you like me?”.

I was so desperate for external validation I think I would’ve done anything for it.

The pernicious racism of the culture I grew up in (rural England) reinforced that my value in all ways (including, and most importantly to me in my teens, desirability) was at a deficit by virtue of my skin, and blood, and mother, and so I’ve spent years trying to learn my own intrinsic worth. I hadn’t worked that out back then.

‘Likes’ were - and I am sure still are - addictive to someone who needs validation as much as they need food, and so the more I got, the more of that I would post. Landscapes, sunsets, food - they were not hitting. But the less and less I wore, the more likes I got until I could expect several hundred, if not thousands per post. The effect, I’ve felt since then, was not unlike grooming. I would not have been able to post a bikini pic on day 1, but the more I grew to need the double-tap of strangers, the more I was willing to do for it.

What complicates all this is that, at the same time, I was doing a lot of quite serious feminist work. I went back to the UN to speak about feminism for a second time, and after that I was my university’s lead speaker for their 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence. I posted “stories” about this time on my “.fit” account – the same account I was posting sexualised pictures of myself on.

So, how did I make posting self-sexualised content congruent with the pursuit of feminism?

“I am reclaiming my body. It’s empowering.”

It was quite a common thing to think and say back then and to be clear, I don’t disagree with the sentiment. It does feel powerful to be sexy of your own volition. But where I get tied up is why we think it’s empowering – and whether it actually can ever be of our own volition.

I want to talk about what empowerment means. If I asked you to give me a full definition, I don’t think you’d find it as easy as you imagine.

In feminist academia, they’re really not much clearer. Some people think empowerment is a process; some think it’s an outcome. Some say it’s a reflexive process where an individual seeks power whereas others say it’s a fundamental change in consciousness required for social action. Some say it is literally any transformation of an individual even if that transformation is detrimental to others - even if that means inconsistent ‘empowerments’ between individuals.

The problem with most of these definitions is a focus on the individual. Inconsistent ‘empowerments’ stall political momentum - empowerment is not empowering, it’s self-serving; ‘every woman for herself’. I just don’t get that neoliberal individualistic “if I want it, it’s good” mindset. Empowerment must have a collective focus in order for the empowered person to have any agency. Think about it. Empowerment has to be an interpersonal process - personal power doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it’s in the eye of the beholder.

There’s a definition of empowerment I’ve come to really like: “empowerment is an inherently interpersonal process in which individuals collectively define and activate strategies to gain access to knowledge and power” (Summerson Carr, 2003)

So where does self-sexualisation fit into this?

Let’s take Kim K as an example.

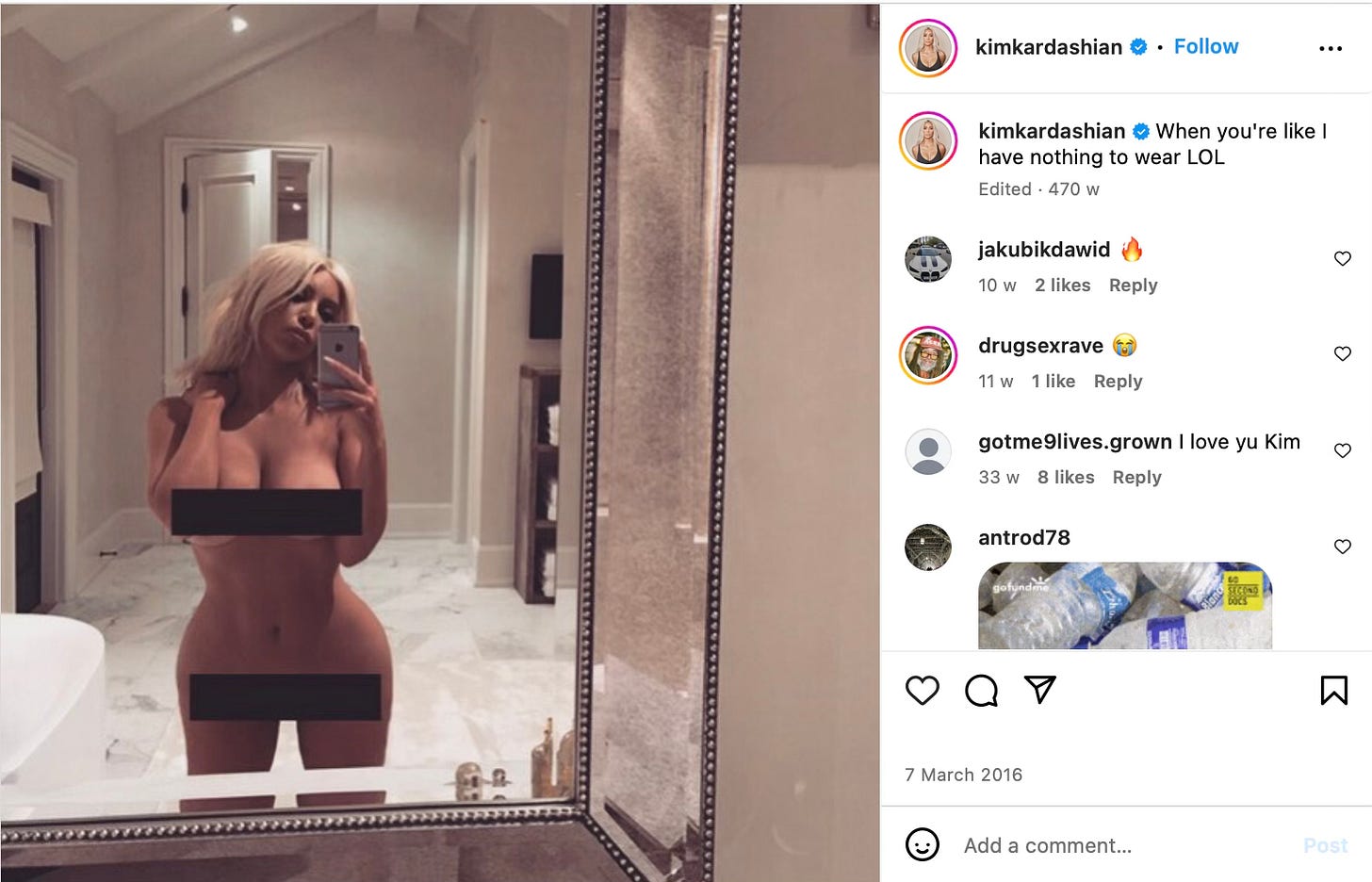

On 7 March 2016, Kim posted a nude photo on Twitter captioned: “When you’re like I have nothing to wear LOL”. You’ll probably remember it - people were really mad about it. Chloe Grace Moretz got involved for some reason. But the image serves as a perfect example of how, when women self-sexualise, people have incredibly varied reactions.

Some argued that Kim’s choice to post the photo on her own terms subverted traditional norms and reclaimed her sexuality. Think about John Berger’s critique of how women’s bodies have historically been controlled: “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting ‘vanity’” (Berger, 1972). Is Kim’s reclamation of her body - one that has inarguably been commodified for her whole career, starting with her sex tape that brought her to fame - actually empowering, because it’s hers to do with as she likes, and she is doing so?

Alternatively, Jameela Jamil called the Kardashians “double agents of the patriarchy”; they promote unattainable beauty standards while profiting from diet products and cosmetic procedures. Despite their claims of body positivity, the Kardashian brand reinforces a culture where women are expected to shrink themselves - both literally and figuratively - to fit patriarchal ideals.

The Kardashians embody the neoliberal idea that an empowered woman is one with money and personal ambition. Their brand thrives on controversy, using provocative images to stay in the spotlight. Kim posted this to make money, not to depoliticise female nudity.

True empowerment should give political agency to women as a collective—not just serve an individual’s brand while reinforcing the very structures that limit women in the first place.

I’ve said “neoliberalism” a bunch already, so let me explain. Yes, neoliberalism is a system where free markets reign supreme, prioritising competition and profit over social issues like racial or gender inequality, poverty, and environmental damage. But it doesn’t just shape state policies; it controls how individuals think and act. Instead of a collective society, it turns people into individual entrepreneurs and consumers.

This makes the idea of neoliberal feminism seem almost oxymoronic - if only. Neoliberal feminism exists and takes the language of traditional liberal feminism—equality, opportunity, empowerment—but strips it of its collective and political meaning. Instead, it focuses on individual success and self-optimisation, turning feminism into a personal, entrepreneurial pursuit.

The ideal neoliberal feminist is someone who balances work and family life seamlessly, and any individual effort toward achieving this is seen as a feminist act. The problem? Systemic inequality is acknowledged, but then dismissed as a personal challenge rather than a political issue. Social justice is reduced to self-improvement, rather than collective change.

You see it everywhere: “girlboss” culture; campaigns telling you “you’re beautiful just the way you are” as long as you buy this exact moisturiser; or high street brands selling slogan tees that say, “Empowered Women Empower Women”, made in sweatshops by women on slave wages. It’s feminism corrupted for profit, stripped of any threat to the system it claims to challenge.

So, is self-sexualisation genuinely empowering, or is it just another product of neoliberal individualism?

Well, let’s look back at my fitness influencer days. I was posting solely what would get me more likes on Instagram, which led to a spiral of self-sexualisation as like-chasing. Why did this happen? Because Instagram algorithms are trained to keep your attention on Instagram, so that it can advertise to you more.

And a near-naked teenage girl does that better than sunset pics. So, in short, I was turned (and I turned myself) into a commodity to make Instagram more money while I used the language of empowerment to justify doing so. If I had been more popular, I could have monetised my account to receive some of that money myself, but I gave up before then. I cannot see anywhere within this story where I was actually empowered. My political agency, if anything, was undermined.

What I think is fascinating about this is that, despite the Instagram, Kim K, and neoliberalism of it all, this is a really really old problem. Mary Wollstonecraft wrote about it in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792:

“Taught from their infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison.”

Wollstonecraft was arguing that her contemporaries had internalised patriarchal expectations, valuing beauty and passivity because they had been conditioned to do so. They unknowingly reinforced their own subjugation, believing they are making independent choices when, in reality, they are confined within societal expectations.

The challenge, then, is recognising when your chosen so-called ‘empowerment’ is truly liberating, and when it is simply repackaged conformity.

Let’s go back to that empowerment definition I like: “empowerment is an inherently interpersonal process in which individuals collectively define and activate strategies to gain access to knowledge and power” (Summerson Carr, 2003). True empowerment MUST be collective. It cannot be defined by personal gain alone, and so in the existing power structures, genuinely and legitimately feeling powerful because you feel desired cannot, in my opinion, be called empowerment.

Because that feeling of empowerment you get through self-sexualisation is the feeling of your “value” increasing in a patriarchal system – it is not the feeling of increasing of your political or agentic power.

This does not mean that women should be shamed for participating in self-sexualisation, nor does it mean that sexuality and feeling powerful are inherently at odds. However, if self-sexualisation is spoken of in the language of empowerment, then we have failed to expand the definition of power beyond patriarchal terms.

Empowerment cannot be measured solely by personal satisfaction - it must be assessed by its capacity to expand freedom for all women. If empowerment is confined to the self, it is not empowerment at all, but an illusion of progress within the boundaries of an oppressive system.

Women are so much more than their innate sexuality. We are so much better than pimping ourselves out to algorithms. We are not just individual consumers - neoliberal agents - assured that we want is inherently right, never mind who it hurts or what it means for the women around us.

If I could go back to my 19-year-old self and tell her one thing, it would be this: desirability is not power. Desirability is the metric used to value your worth in a system that has preordained you to be less than you can be. Be beautiful, by all means. Be confident. Be powerful. But above all, question what it is that makes you feel those things – and who benefits when you do – because if your power depends on being looked at, it was never really yours.

nice read and very well written! you got it right: if women were truly empowered in neoliberal capitalist societies, they wouldn’t need to sexualize themselves in search for validation and profit. if the body of a woman is turned (or has to be turned) into a product, for the eyes and pockets of men, primarily, that means they don’t really hold the power they thought they had, even if they made this choice willingly.

great essay!!! love love love